Welcome to new subscribers! This is Revisiting Britain, a series where we go back to people and places experimenting with ideas about ownership and development in the UK. So far we’ve caught up with projects around forest stewardship, taking on empty high street buildings and challenging landlordism in central London, and today we’re heading to some china clay mines in Cornwall. The newsletter is free but the labour isn’t, so if you like this, do send on to other potential subscribers, or comment, or “like” the post. It’s always nice to hear from people.

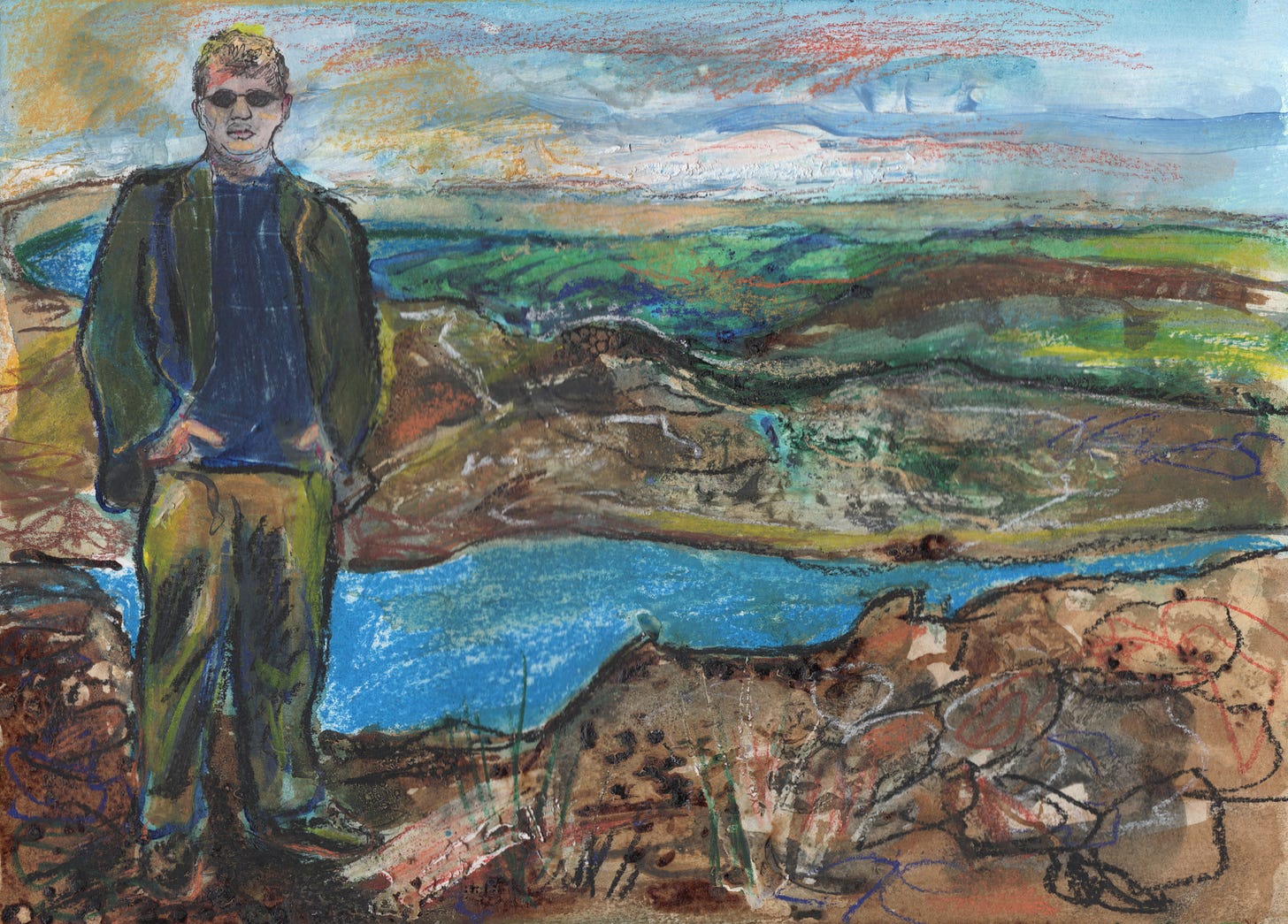

The rise and fall of clay mining has shaped the fortunes of the Cornish town of St Austell for hundreds of years. Local people live in the shadow of the giant flat topped mountains, iced in white china deposits, left behind from former brickworks like Wheal Remfry, which closed in 1971. Dense brush has grown over the old buildings, covering clay-firing kilns and rusting mining equipment. Water has filled the old pits, creating startling blue mineral pools surrounded by a quicksand-like clay slurry made of mica, a waste product. Aside from a handful of nature trails, the former mining sites are forbidden to locals.

Four years ago, Alex Murdin told me about Clay Town – a vision of bringing local people closer to this post-industrial landscapes with art. It has since bloomed into an economic plan for the town, centred on St Austell as a hub for the ceramics industry, with workshops for tourists, education programmes and a series of installations and exhibitions. Here Alex talks about the idea of cultural-led regeneration and some of the challenges involved.

Interviewed on September 5, 2017

The economic development plan has been written and has been circulated more widely. It’s an interesting plan – I’m biased! – but I think it is interesting because it takes the idea of place and culture as the foundations and looks at integrating it more closely into an economic plan.

There has been this original Clay Town vision for some time. We’re keen to have the strategic stuff but also to have grassroots support. The culture and the art is a tool for engaging people in the regeneration in St Austell. It’s about getting people to participate and make things with clay.

We’re using clay as a tool to discover how people feel about this as a place, and what they see as part of the vision. It’s this idea of cultural-led regeneration.

The White Gold Festival will be small this year. There are three practical workshops. We hoped to use Raku firing, a Japanese technique, it’s a way of getting a smoky glaze on pottery by dunking it in blazing sawdust. We have an international maker for the first time, a Turkish ceramicist. She is making traditional clay ovens and they are taking them down for the festival and making food in them as well. We’re trying to incorporate elements that are important locally – food, agriculture – but in a neutral way, not a political way that polarises opinion. And then a craft fair and other bits as well.

We’re trying to establish a core audience in the locality, covering a fair chunk of Cornwall. We’re building towards a partnership with the Stoke Ceramics Biennial. They’re working towards a city of culture bid in 2020 or 2021.

The idea is that we’ll join with them in a bigger project with an international dimension, making contact with china clay producers and bringing them over.

We have a broad-brush plan within the Clay Town vision to meet with the ceramics biennial and working with them on marketing, doing a bit of cross marketing and engaging audiences nationally.

There is fantastic support from the community to do this. They have a catalyst in Tim Smit [founder of the Eden Project]. He was a major spark, but the business community in particular have come on board. For the festival we have St Austell Brewery, the College of Art, Imerys, South Lakes West Trust who run the water areas, the St Austell Bay economic forum, we have the town council and the business improvement district.

I’m a weird specialist in that sort of area, I have a PhD in research about cultural regeneration and rural art, and how culture can support rural spaces.

Art tends to be under-provided in rural areas, which is being picked up more generally, the arts council are giving support for the regions.

Places like St Austell that have serious levels of deprivation are not treated as seriously as inner city areas. There are ideas about food or cultural tourism gaining traction to make these places attractive areas to live, otherwise you end up with dormitory towns or places for second homes, where they lose their cultural authenticity.

The irony is that the more visitors you get, the less it feels like a real place to live in, so it’s about reinforcing that sense of identity.

Interviewed on March 9, 2021

We have made some good progress. We started off with a very small festival in the summer, White Gold festival, with Imerys, the clay manufacturer, Eden Project, the brewery, a print company – they all came into the town centre and put up stands and there were speeches and entertainment.

Since then we got some investment from the arts council and we were able to expand the festival. The last physical one in 2019, we had 12,000 people, which was very respectable.

We were doing clay and ceramics, quite hands on – but also using it as an opportunity for them to talk to us about what they want and to get stories about what they were proud of in the area.

I remember a lady in her 70s talking about what she did in terms of the clay industry, what her husband did, and how proud she was with that kind of heritage and history.

In 2018/19 we managed to get a grant from the Coastal Community Fund of £1m, plus £300,000 from Cornwall Council, half for White Gold and half for greening projects. We have a garden curator working on a project to make the A391 into a wildflower corridor, working with the Eden Project, which is now the home of the National Wildflower Centre.

Ceramics has focussed a lot more on the town centre. It’s always needed a bit of tlc.

A new shopping mall was built in 2008 but it’s never been fully occupied and now they are trying to sell it. We are focussing on the town centre and saying that the story is doing things differently, in the Cornish spirit. So we have commissioned 14 artists to create art around town about china clay. A mural of honey bees was started in 2018 at the festival by the artist Parasite. They basically set up a stall and got people to draw in clay what they loved about Cornwall and Str Austell.

People said they loved the Sky Tip – a waste tip in the hills around St Austell. It’s a bit of a landmark, you can see it from 20 miles away. It’s ironic that this waste tip has become a landscape feature.

In 2006, Imerys were meant to remediate the land, to fill in the tips, and they said, we could take the sky tip down and level it but there was a massive public outcry so they have stayed.

We’re also doing lots of community projects. The biggest one is Brickfield. An artist very interested in brickmaking, Rosanna Martin, is using bricks as a way of looking at heritage but also engaging people in something hands-on.

A brick is an ordinary thing but very accessible. It’s not arty pots or something. They have been based in one of the pits and firing the bricks in a bee-hive kiln that they have made.

Bricks are symbols of infinite potential.

Now they are moving into a phase about how to make things out of these bricks, made from local St Austell Clay. Which is quite cool.

St Austell has its fair share of unemployment and associated problems like teenage pregnancy. There is a big homelessness problem as well. I think we need a few more years to see a change in attitude. That’s been exemplified by the coverage around the sphere sculpture we have installed in the town centre. People say, “Why are you putting it here? It will be trashed. It will be ripped down.”

People have this mentality that we don’t deserve anything, we’re not worth saving.

That’s the purpose of these interventions, to say, you do have something to be proud of, St Austell is worth investing in.